SHOPPING WITH UKUMU

I have mentioned Ukumu several times, of the many ways he helped us to make bus connections in Uganda, and how well he worked with Kakura and Lainya at the press. Since our return after the rebellion, I had been re-assigned to be the director of Editions CECA which hadn’t been looted at all. Lainya and Kakura had taken the initiative to keep things running, and Ukumu had imported paper from Uganda with his pick-up truck.

Before the rebellion there had been many missionaries who could help with the purchasing of goods for the press and the scheduling of travel; now we were without those services so we relied on those among whom we lived.

Ukumu lived in Ndrele, seven kilometers north of Rethy. Most of the people there were from the Alur tribe and many of them did business in Uganda traveling through the Mahagi-Goli border post or some other back road where smaller vehicles could cross. I needed help. The customs fees there were far less, unofficial, and not receipted.

Ukumu arranged for a trucker from Ndrele to provide transport from Pan Paper back to Rethy. His four-ton truck could carry a supply of paper for the press that would last for a year, probably a lot longer since we had lost all our missionary customers.

We repaired the Toyota pick-up’s bald tires the best we could so we could drive it to Kampala to have a new set mounted. Even with a boot, glued inside the worn spare tire, under the bulge, we knew it would be unreliable. We patched the tube using contact cement and a piece cut from another tube. The spare held air.

We had a trip of about 500 kilometers before us, the first 40 kilometers of dirt roads in Congo we would creep along riding the ridges or driving in and out of dried mud-holes. Though the tires would flex a lot, they would not overheat and the patches would probably hold. The risk would be after Murchison Falls park when traveling on the highway between Gulu and Kampala during the heat of the day.

It was late at night when we arrived at the place Ukumu had selected for us. The Alur from Ndrele always used these rooms, deep in the center of the city. The armed guard at the high iron gate greeted Ukumu, clearly knowing him well from previous shopping trips to Kampala. Our nearly empty pickup truck tilted strangely, wobbling along unevenly as I drove slowly through the gate into the safe enclosure. Ukumu had no doubt given the Alur guard some information about his missionary guests, along with a brief explanation as to why I was driving with a flat tire casing, flopping around, loose on the rim.

As anticipated, a tire failed when traveling at highway speeds on the bald tires that had caused the rebels to abandon the truck in the first place. We changed the blown out tire, replacing it with the spare we had repaired. We slowed down, hoping it would last the rest of the way into Kampala. It didn’t. In the suburbs that tire also failed. Maybe we could get there, driving at a walking pace, just off the edge of the road with the rim grinding in the dirt. There was nothing else we could do.

Shortly, two smartly uniformed policemen walked across the road signaling us to stop. Yes, we knew the tire was flat. Yes, we understand that it could be dangerous. Forgive us, but we are limping along slowly, trying to get to Kampala, where we want to buy new tires. We have come nearly 500 kilometers from Rethy, in the Congo. No, there are no tires for sale there. May we continue to limp along? The tires will be replaced tomorrow.

We were allowed to continue limping along and had finally arrived at what I am sure were the least expensive lodgings to be found in Kampala. The guests had small basic rooms on either side of a long hallway. All was built of cement and the afternoon heat radiated from the walls. The shared bathroom was at the end of the hall. Moving our beds next to each other failed to give us a good night’s sleep, but the morning meal, at the restaurant Ukumu favored, was excellent. We may well have been the first missionaries to stay the night at those lodgings, and to so much enjoy the morning meal that was provided.

Ukumu accepted the keys of the blue Toyota pick-up. I left him money, telling him to do everything necessary, to get the truck repaired and back to Rethy. I don’t know how he got the truck out of the safe enclosure to a garage, or even if he went to a garage. More likely, he found some Alur friends to take him to buy the tires and tubes, and then came back with them to mount the tires themselves. They probably washed the truck too. Shopping with Ukumu had the invaluable benefit of him bringing his friends with him. Working together in harmony, each doing what he knows and loves to do, can’t be bought. It was wonderful to trust him.

Ukumu got a friend to take us to the Kampala-Nairobi bus that would drop us off at the Pan Paper mills at Webuye, Kenya, just across the Uganda border. I was eager to visit the factory to see how paper was made and to place the paper order so the already waiting truck could be loaded for our return. Ellen was more interested in visiting with Cathy Clements, the daughter of our good missionary friends at Rethy, now a short term missionary herself.

I found that the logs to be ground into pulp were from fast growing cypress trees that had been harvested from tree farms in Kenya. Three-foot tree sections were moving from the receiving-cutting area along a log conveyer system that started as a wide, gradually narrowing trough, with a moving drive chain at the bottom. The sections eventually oriented themselves, to follow each other into the grinder where the bark was ground off to make the darker pulp for wrapping paper and the peeled section was then ground up for white paper. Making additions of chemicals and other ingredients to the huge vat of pulp, reprocessing, straining, and adding water to attain the desired consistency was the work of highly trained technicians. These were mostly Europeans, hired specifically for their skills, who lived in special housing provided at the plant. The pool, gym, and exercise facilities were for their use. I found they played badminton with such skill and fierce competition that it didn’t resemble the yard game I knew at all.

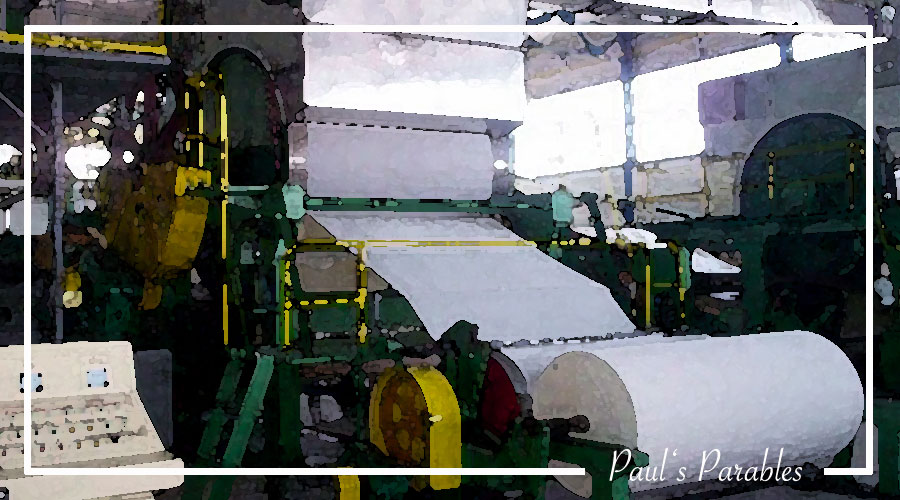

The two immense machines that received the light grey wood pulp at one end, and from which the several hundred pound rolls of paper were removed at the other end, ran continuously. The wood pulp sprayed through a long row of regulated nozzles down onto a wide porous sheet that ran around two widely separated rollers. Water was drawn out with a partial vacuum leaving a thin layer of pulp mud that followed the unending ribbon of material that was fed across a small gap, to then pass beneath a highly polished roller that gently squeezed out more of the excess water. The many rollers that followed repeated the process with ever increasing pressure and added heat, until the layer of pulp had become a continuous four-meter-wide sheet of paper coming from the machines. The paper would then be cut into sheets or rolled into different width cylinders of paper to be sold.

The skilled monitoring of the machines insured that the incoming flow of pulp never varied and that any coatings added to the surfaces of the paper produced the desired results. It took a tremendous amount of work to restart the equipment if the endless sheet of paper became separated. I was fascinated by the machinery but had to follow-up our paper order, so we could get a good start back to Rethy.

The truck driver cared for the loading and soon we were traveling at highway speeds across Uganda. We had traveled for several hours when the driver began to slow down. We were approaching a police check. An iron spike bar, which blocked our entire lane, was clearly designed to destroy the tires of any vehicle that failed to stop. The police just dragged the device into the road when they saw a vehicle approaching that they wished to stop and inspect. Before our driver got out to speak with the policemen I heard one allege that the tires of the truck were worn out.

The driver solved the problem by talking with them behind the truck, and returned to climb into the driver’s seat and continue our journey. It wasn’t long before exactly the same thing happened again. I wondered if the policemen recognized the truck and knew what the driver would offer, to pass the inspection. I discovered later that the driver had some sort of expense account to deal with this sort of situation, because he was agitated when he saw that the next police agent was a woman, and apparently one he had never seen before. “The women are very tough”, he said.

He tried the same procedure but returned from behind the truck to tell me that the woman was very unreasonable, and wanted a 15,000 Uganda Shillings fine to be paid. He didn’t have enough money. He had offered 2,000, but she had refused. I guess both expected the white man to have plenty of money to pay, and then we could simply continue on our journey.

I refused to hand over the cash and she insisted that we were required to go before the magistrate at the court three kilometers down that side road, if we failed to pay. I agreed to go to court and, hoping to shame her into becoming more reasonable, began walking briskly down the road towards the courthouse. It didn’t work. She told one of the passengers in the cab to climb up on the load of paper and insisted I squeeze in beside her for the drive to the court.

The hearing was a solemn occasion. The driver stood in a cage-like docket at a level below the pompous robed magistrate, looked up and was forced to agree that the tires were, in fact, worn out. The details were entered in a huge ledger that covered the entire desk. The fine was assessed at 15,000 Uganda Shillings.

I agreed to pay, but did plead for permission to travel to our destination where the owner of the truck would certainly replace the tires. It was my load of paper and must not be delayed or damaged. More notations were made. I had a feeling that the entire exercise was designed to collect heavy fines and that all present, except us, would profit.

The 15,000 USH was duly paid to the court. No receipt was offered. I insisted that my business had to have receipts for all expenditures and after some discussion, in some other language, the secretary wound a sheet of paper into an old Remington Rand typewriter and typed the official receipt, signed, and even sealed it with an official stamp at my request.

I expressed surprise that they didn’t have a large Uganda government book for preparing triplicate receipts. I would be glad to print a receipt book at Editions CECA for them, but would need a print order and sample from the authorities in Kampala.

All of us were in the truck preparing to leave when the secretary came running out asking that I return to the office. “There has been an error!” she said, “Bring back the receipt.”

They did have an official receipt book that nearly covered the desk when opened. It had quadruplicate copies of different colors with the information transferred automatically to each copy below. I received my customer copy and we again squeezed into the cab, hoping to enter Congo customs before dark and get to Rethy, if possible, the same day. That fine would now have to be shared with other authorities in Uganda.

The driver Ukumu had hired was driving a truck with bald tires. They did need to be replaced. After having paid two bribes, and a large fine, he would avoid daytime travel back to Kampala for a while.

Crossing through the Goli and Mahagi customs posts with the help of our Alur driver proved to be without complications. The receipt I was able to get, for the millions of Zaires paid in customs, was hand-written on the corner of a notebook page by a very heavy, smiling, sweating soldier. He tore off the corner and gave it to me. I have no idea what his status was in relation to the new government established by Kabila, but the Editions CECA treasurer, Kakura, would understand and staple it to the import documents.

The receipt, with smudged ink on the official ink stamp, was easily explained. I had gone shopping in Africa with Ukumu.

God had used him to help me accomplish the task that had been assigned to me.